BLOG

Tina Gudrun Jensen, researcher at MIM – Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, Malmö University and ReROOT coordinator of arrival integration research.

On November 7, 2023 MIM – Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, Malmö University, which is part of the ReROOT team, held a Symposium on perspectives on the EU´s New Pact on Migration and Asylum in Brussels.

The New Pact was initially proposed in 2020 and negotiations are due to conclude in February 2024. The aim of the New Pact is to find a common EU framework for migration, a set of regulations and policies to create fairer, efficient, and more sustainable migration and asylum processes for the European Union. The New Pact entails new asylum and migration management regulations, a new EU asylum agency, uniform rules on asylum applications, new rules governing migration crisis and force majeure situations, a new screening regulation, supposedly better reception conditions, an updated EU fingerprinting database, a common asylum procedure, and a new EU resettlement framework.

The panel members for the symposium in Brussels were Johan Ekstadt, doctoral researcher from Dept. of Global Political Studies, Malmö University, Magdalena Ulceluse, assistant professor in International Migration and Ethnic Relations at MIM, Malmö University, Dr Basak Yavcan, head of research, Migration Policy Group and Dr Hanne Beirens, Migration Policy Institute Europe.

The panel debated the positive and negative aspects of the New Pact. On the positive side, the panel mentioned that many member states were willing to come to the negotiation table and collaborate on the New Pact. Yet, the panel also pointed out many shortcomings of the New Pact. Generally, the panel members questioned whether the New Pact will resolve the core problems of the asylum system. They pointed out that as more administration and decision-making will happen at the border, even more people will be stuck at there. This is in line with a general critique of the New Pact that procedural rules appear to be so complex that they may be unworkable in practice. Consequently, the new procedures may lower the protection standards for asylum seekers in Europe as it is expected that there will be more use of the border procedure, which will lead to more people in detention centres at the external borders, and thus to substandard asylum procedures and more pushbacks. Also, the New Pact does not do away with the system of the Dublin regulation, i.e., migrants can still be sent back to Greece.

Another criticism that the panel raised was that the New Pact does not put priority to special vulnerable groups such as children and victims of domestic violence. This also reflects a general criticism against the New Pact for not considering exemptions from the border procedure for vulnerable people. Furthermore, the panel pointed out that regular migration related to labour as well as low-skilled migrants has little priority in the New Pact, which appears to prioritise only the `best and brightest´ migrants.

The change in EU policy represented by the EU´s New Pact on Migration and Asylum is important for the ReROOT project, which has a focus on the development of migration regimes, and provides insights into arrival processes as they take place within policy contexts. The ReROOT project is concerned with the many constraints in migration and reception systems, and hence observe any changes that may improve the involved procedures.

Share

Márton Bisztrai | Menedék Association | 30 May 2023

Within the ReROOT project, our team at the Menedék Association focuses on the arrival infrastructure of third-country nationals in the Hungarian higher education system. These arrival infrastructures do not emerge in a vacuum but in a specific atmosphere of Hungary’s migration scene. This blog will present the different interests of two major political areas setting this scene, e.g. 1) the area of ‘migration’ power politics and 2) the area of migration realpolitik.

It might be confusing that one will not find two opposing entities behind the duality of seemingly controversial areas. Instead, it is the same united political power, FIDESZ, the governing party.

The media and political decision-makers often interpret Hungary’s migration atmosphere incompletely. In most cases, the statements are driven by morality, political agendas, and ideologies. For instance, voices that criticise the Hungarian government often use expressions like “anti-migration regime,” “evilness,” “political schizophrenia,” or “cognitive dissonance” – just as if we were dealing with a “lunatic.” Pro-government supporters comment on the same acts with words such as “braveness,” “defence,” “patriotism,” and “nationalism.”

Nevertheless, from our perspective, there is no cognitive dissonance within this unity. Rather, we witness the – in terms of their interests – logical behavioural patterns of the government.

Area of power politics – thematisation of public opinion

This consists of the tireless and continuous one-way political campaign (since 2015) that is aimed at the public. It refuses and stigmatises “migration” and discusses it in a framework of fear, national sovereignty, and conflict (or even war) of civilisations.

The propaganda tools and resources used by the government in the last eight years are countless. Here we show only two of these examples (one of the earliest and one of the latest) to illustrate the intensity and rhetoric of Orbán’s power politics.

In the spring of 2015, under the umbrella of National Consultation, the government sent a questionnaire to Hungarian households with the eloquent title Immigration and Terrorism. One example from the twelve questions: Did you know that subsistence immigrants cross the Hungarian borders illegally, and in the recent past, the number of immigrants in Hungary increased twentyfold?

And the results were: 72,63% marked the answer Yes, 23,45% I have heard about it, and 3.91% marked I did not know.

In July 2022, at the youth-political-cultural summer fest in Tusványos (Romania), Orbán gave a one-hour speech to the public. He mentioned migration among the most pressing challenges that the country is currently facing. And he went further.

“The internationalist left has a trick: they claim that nations living in Europe are originally mixed race. This is a deception because it bonds different issues. Because there are places where the European nations are mixing with those who arrive from outside Europe. Well, this is the mixed-race world. And we are here where European nations are mixing with each other. This is why, for example, in the Carpathian Basin, we are not mixed-race, only a mix of nations living in their own European home. (…) We are willing to mix with each other, but we do not want to become a mixed race; this is why we stopped the Turkish in Wien, and if I am right, this is why the French back in the old times stopped the Arabs at Pointers.”

These question-shaped, contextless statements, Orbán’s speeches and all the other propagandistic elements applied by the government are logical and play well in the power politics, from at least two angles. First, a mass of citizens, supporters, and potential voters resonate with it. And second, it is suitable to overshadow pressing and uncomfortable political and socioeconomically questions.

The message is that “migration is bad. Therefore, we must prevent and stop migration and not support or manage it.” This political discourse (in this case, the one-way delivery of messages) dominates Hungary’s public opinion.

Power politics use “migrant” or “migration” arbitrarily. It links them with concepts of illegal border crossing, non-Christian, non-European, non-white intruders, potential criminals, and essential threats.

The strategy proved to be successful. In 2018 and 2022, FIDESZ won the parliamentary elections by an overwhelming margin. Using “migration” helps them to create an ongoing conflict (a ground where they communicate power and success) with the EU authorities, civil society, and other Hungarian political parties. They successfully keep alive the concept that Hungary is under constant attack, and only the current regime can repel it. Illusion, perception, reality, lie? Not relevant. The only relevance is its extreme success.

This strategy defined the last years with such power that government could not stay only in the fields of symbolic propaganda and noise-making. The messages appeared in the legislation as well, matching the atmosphere created by these symbolic messages. For example, in 2016 Orbán initiated a constitutional amendment. The draft included such lines as Alien nations cannot settle in Hungary. In the end, the proposal did not receive the needed parliamentary support. Therefore, in 2018 the “Stop Soros Amendments” took place, which have three major elements: “(a) The law on the social responsibility of organisations support illegal migration; (b) The law on the immigration funding levy; (c) The law on immigration detention.”

The same year the government blocked civil society organisations and other service providers access to the EU’s Asylum, Migration, and Integration Funds.

It is hence not surprising that the number of refugees has dramatically declined. Since 2000 the authorities have recognised the international protection need for approximately 10 000 people. According to the last (2022) statistics, 2 500 remained in Hungary. At the same time, however, the appearance of propaganda symbols in legislation did not curb the number of newly arriving foreigners. There are no less veiled Muslim women taking their children to the playgrounds in Budapest or no less Sub-Saharan African men walking in countryside towns. There are no fewer Iranian tenants in Budapest’s rental sector, and the Georgian, Vietnamese or Mongolian workers have not disappeared from the construction sites of the priority industrial investments—instead, the contrary.

The Central Statistical Office says that in 2015, 145 000 foreign citizens were living in Hungary, and by 2022 their number was 202 000. The increasing arrival of third-country nationals primarily causes the 40% growth.

The second competitor: the area of realpolitik – interests, needs, and solutions

The area of realpolitik concerns political actions, responses, and solutions that are based on economic needs, demographical trends, and diplomatic challenges. Whereas in the area of powerpolitics the government successfully uses (abuses) the word “migration” when engaging with its potential voters. In other segments, realpolitik uses, encourages, and organises migration to respond to demography-related economic challenges. First of all, Hungarian society is ageing. During the last forty years, the population decrease has been permanent. Secondly, according to the estimation of the Statistical Office, 350 000 Hungarian citizens left the country during the last ten years. The UN International Migration Stock estimates a higher ratio. And lastly, approximately 15 000 Hungarian youths are enrolled in foreign higher education. As a result, state investments, industry, service sector, agriculture, and food industries face labour shortages. Therefore, it is unsurprising that inbound labour migration has grown parallel to emigration. In 2015 the authorities registered 39 000 foreign workers. In 2022 under the same legal framework 74 000 people were registered. During the same period, the number of international students increased by 50%, from 20 000 to 32 000. Behind this significant growth is the state that stepped up as the primary recruiter.

For example, in 2013 the Hungarian government announced a large-scale scholarship system called Stipendium Hungaricum that offers education programs in local universities to third-country nationals. Currently, 12 300 scholarship-holder students (primarily from the Middle East, North Africa, Post-Soviet countries, and South East Asia) study in universities in Budapest and rural towns.

Stipendium Hungaricum is neither initiated nor led by the universities or representatives of education politics. Instead, it is driven and implemented under the control of the Foreign Ministry and the umbrella of the “Opening to the East” policy in the form of bilateral interstate agreements.

Whereas power politics symbolically and physically blocked the asylum channel from Syrians, Yemenis, Iraqis, Kosovars, Pakistanis, Nigerians, Myanmarese, Iranians, etc, the student mobility channel has been opened to young citizens, often from the mentioned countries at the same time.

Stipendium Hungaricum beneficiaries receive tuition-free education at undergraduate, master’s, and PhD levels. The language of study is English, and monthly financial support is also part of the package.

Meanwhile, foreign relations within the EU are worsening, and diplomatic links are strengthening outside the EU. Although the quality of higher education (with few exceptions) is not in competition with Western institutions, the spread of English-based education resulted in organic development. It attracts more and more fee-paying international students. International students as a whole (Stipendium Hungaricum, Erasmus+, fee-paying) create financial profit for the national economy.

From the perspective of many applicants, the advantage of the Hungarian offer is the English curriculum, the stipend, and that “Hungary is Europe.” Although Hungary is an arrival country towards a Western European context, more students try to prolong their stay here by continuing studies at a higher level or searching for employment. This phenomenon may contradict the original concept of the scholarship. When launching the program, the Foreign Ministry made the objectives clear: students return to their home countries after graduation, help to develop bilateral diplomatic relations, engage in transnational economic or academic activities, and in general, spread the good image of Hungary. The long-term integration of foreign students was not on the agenda.

In conclusion, power politics dressed in an ideological costume and realpolitik compete. The slogans used in Orbán’s rhetoric – like “mixed race” and “If you come to Hungary, you cannot take the job of Hungarians” – echo in other fields of migration. At the same time, realpolitik is working behind the scenes and, for example, introducing changes in the immigration policy that make the students’ transition easier towards the labour market (however, still tricky).

The Hungarian government supports and organises the arrival of third-country nationals in some areas, for example, in higher education and the labour market. It is a benefit-oriented, highly controlled form of migration that keeps people in a state of temporality. Created by realpolitik, several entry points and migration channels led to Hungary. At the same time, an anti-integration ideology is in place (painfully visible in the public rhetoric). Both of these areas are blocking the settlement, permanence, integration, and “mixing”.

Share

By Tamlyn Monson I Coventry University | 11 May 2023

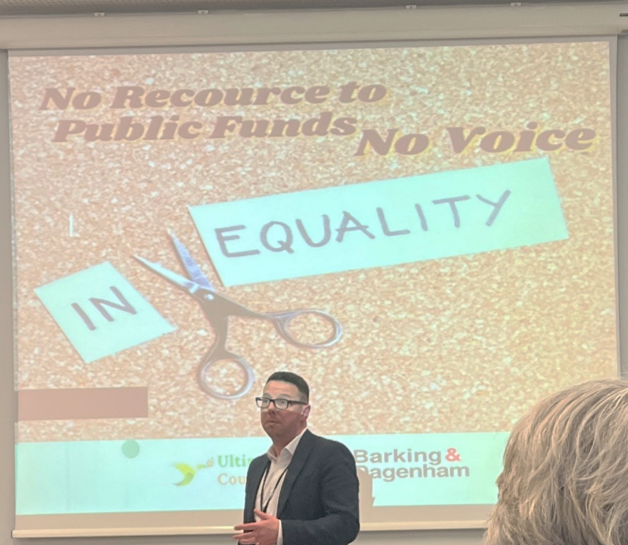

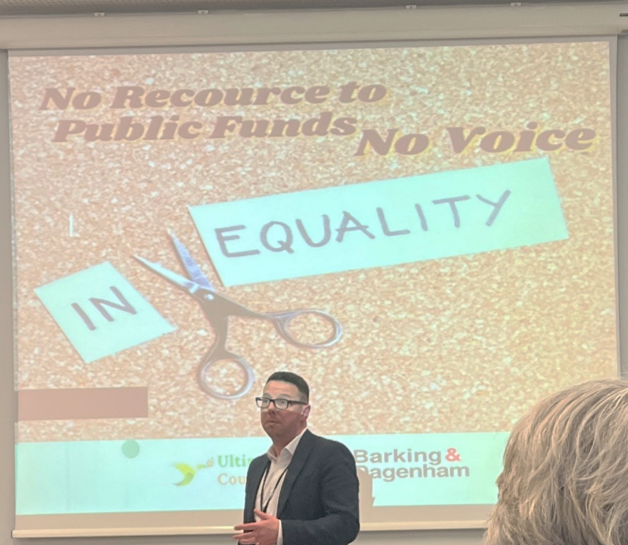

Wednesday 26 April 2023 saw the launch of a guidance document on supporting Barking & Dagenham residents who are subject to the ‘No Recourse to Public Funds’ (NRPF) condition. The audience included representatives of the council and voluntary sector, and a number of residents with lived experience. I was among several members attending from a local network aimed at improving support for migrants in the borough, an initiative supported by BD_Collective – a network of networks that supports change in the borough. Also attending were members from various local community and support organisations, including Ultimate Counselling, The Source, Community Resources and Marks Gate Relief Project.

The NRPF condition is a restriction imposed by the Home Office on immigrants to the UK, which prevents them from accessing the ordinary safety net of state welfare support that citizens and formally ‘settled’ people can if they are faced with hardship or destitution. Being subject to the NRPF condition is particularly difficult for anyone who falls on hard times, becomes homeless, loses their job, or – in the case of an asylum seeker for instance – is not permitted to work due to Home Office Policy. Together with work restrictions imposed by the Home Office, the NRPF condition creates structural inequalities within the populations these organisations serve, inequalities that cannot be fully addressed at the local level, although their impacts are felt locally. So the NRPF condition also poses difficulties for council and voluntary sector services seeking an inclusive approach to supporting residents.

My year of ethnographic research in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham in 2021-22 showed how the needs of such residents often remain under the radar. It also suggested that service providers are often unclear what support is legally permitted, and what is actually available locally, to people with no recourse to public funds. As the first step to fill this gap, this guidance is a cause for celebration. It was co-produced through a Place-Based Partnership of council and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) stakeholders, with Dagenham-based refugee-led organisation Ultimate Counselling leading an engagement with 157 residents subject to NRPF conditions and conducting a survey of 131 frontline staff.

When Ultimate Counselling director Sarah Kasule shared the key themes that emerged from focus groups with residents, I noticed strong overlaps with ReROOT* research findings on barriers and enablers for new arrivals in the borough. I highlight three of them below.

Residents’ Language Capacities

My research for ReROOT found that this is a borough where many residents struggle to speak, read or understand English, but signposting – both verbal and visual – is seldom multilingual. In addition to this, key helplines of the NHS and Citizens Advice Bureau do not feature the option of interpretation before launching into recorded English messages that must be navigated to access them. Hospitals issue jargon-laden letters in English to families who cannot understand their content. Landlords of dispersed asylum housing expect asylum seeker residents to simply sign tenancy agreements written in complex English regardless of their language proficiency. Significantly, against this backdrop, Sarah Kasule announced that this guidance document will be made available in the main languages spoken by participants in the co-production.

Barriers of Knowledge and Digital Access

Lack of digital literacy and lack of local know-how were key blockages which came up over and over again in my research for ReROOT. Sarah Kasule highlighted similar barriers for many residents with the NRPF condition. She highlighted how lack of access to smart devices, data or digital literacy were key barriers to accessing statutory services, and pointed to residents’ lack of knowledge in terms of both what they were entitled to or how to navigate systems to solve housing problems for instance. This resonated strongly with findings from the ethnographic research, where I met people who were unaware that they could access free primary healthcare, or incorrectly believed they could not access the Citizens’ Advice Bureau because the organisation’s name suggested that the service was for ‘Citizens’ only.

The Role of Social Connections

Another finding from ReROOT research was that the right social connections can help offset the barriers of language, digital access and know-how, but that many marginalised newcomers did not have the social connections they needed to overcome these barriers. In a similar way, Sarah Kasule highlighted the theme of social isolation, noting for example that many participants in the focus groups did not have friends or family to help them when they arrived, and that asylum seekers arriving alone in dispersed accommodation were given no support to form connections in the local area . She illustrated the important role of social connections when she explained that knowledge gaps often persist because residents with no recourse to public funds are socially isolated, or because the people that they know are also unaware of their rights and entitlements.

The two hour event was eye-opening for some attendees because it included residents whose lives and challenges are usually out of sight. Single parents had to bring their children to the event, including a child with special educational needs, which brought some noise, challenging behaviour, and interruptions of mothers’ participation. The barrier to inclusion caused by lack of childcare support was tangible. A group of homeless non-English speaking men were present, and an interpreter communicated their desperate request for help with GP registration and more toilets in Barking. The latter request in particular seemed to cause confusion, perhaps because the majority of attendees have homes, and are less dependent on public water and sanitation infrastructure. It was clear that few attendees shared the experience of one man I spoke to during my research. He was sleeping under a bridge, in an area with no 24-hour toilet. At night, when the local shopping centre and library were closed, he would have had no choice but to suffer the indignity of urinating or defecating outside. Yet, rather than empathy, he received a notice that treated these indignities as a form of anti-social behaviour he was committing. He was forbidden to sleep there anymore.

Fortunately, the voices of participants were heard. Head of Universal Services, Zoinul Abidin, responded in closing that the council would consider the toilet question, and would also consider bringing GPs to community hubs to register new patients who were struggling to access them. Together with the commitment by the council’s Director of Community Participation and Engagement, Rhodri Rowlands, to keep the NRPF guidance document alive by revisiting it in 12 months time, it was reassuring to see this expression of Barking & Dagenham’s commitment to the council’s vision of ‘No one left behind: we all belong.’

Share

Footnotes

[1] The Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation (ESTIA), was initially implemented by UNHCR in collaboration with the local authorities and NGOs and funded by the European Union Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid (ECHO). The project provides temporary accommodation for relocation candidate and vulnerable asylum seekers through rental apartments in various parts of Greece. The second phase of the program is being implemented by the Ministry of Migration and Asylum in an effort of centralization of the immigration policy.

[2] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

by Aimilia Voulvouli | University of Thessaly

It is early in the morning in the inter-cultural centre Stavrodromi in Karditsa, Greece, and employees as well as beneficiaries, that is, international protection seekers are frustrated. Stavrodromi, which can be translated as “Crossroads”, is a pilot infrastructure created through the “Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation” – ESTIA[1] program. It is located in the heart of the city, at the Municipal Market which is a bazaar styled structure that hosts public and private businesses as well as a social grocery store, a bar, a small museum, the Red Cross branch of Karditsa, a radio station, a local newspaper, cultural associations and it is generally considered a meeting point by the locals.

Stavrodromi has been founded by the Development Agency of Karditsa (its Greek acronym reads as ANKA) and hosts all the social services of ESTIA. Eventually, it became a point of reference for the beneficiaries. There, they can get social services aimed at them or information on other services they need. It also runs a language school for Greek, Arabic and French. Computer spaces are also available for the beneficiaries to use, as well as a space for women and their children to spend their time creatively.

In May 2022 the last installment of the funding of 2021 has not yet been allocated to implementing bodies such as ANKA. Without these installments, rent and utilities are going to be overdue for the rental apartments that are used by the ESTIA program. A few months ago, the cash assistance program which was initially implemented by UNHCR[2] was taken over by the Greek authorities which also resulted in delays in payment. For about six months now, both employees and beneficiaries find themselves in an indeterminate situation. Employees don’t know when they are going to get paid for the services they have signed a contract to provide, and whether these contracts are going to be renewed. The beneficiaries don’t know when they are going to get their cash assistance or whether their shelters are going to be secure.

“We had to change apartment and live with two more families and now we are told that this might happen again due to financial difficulties. We are like children here who are told what to do. There is no stability”, said Tarik, one of the beneficiaries, during our interview earlier that week in May 2022. Similarly, John said during an informal discussion while he was visiting Stavrodromi to meet up with a potential employer: “My asylum interview is in May 2023, in the meantime I wake up in the morning and I don’t know what’s next. Am I going to have the same apartment? Am I going to be able to find a more steady job? I am now working here and there whenever there is a need for hands from the employers that ANKA is in liaison with. I feel like a child whose everyday life gets dictated by my parents and I have to improvise and be creative the whole time”. On the other end, Maria a psychologist working for ESTIA told me that she has already started looking for a new job because she understands that the stability that she had until now is not going to last long. In an informal discussion I had with the CEO of ANKA back in December, he told me that while they are legally not obliged to continue offering their services since they have not received the agreed amount, they feel morally obliged to do so, for the beneficiaries, the employees and the owners of the apartments they rent. “But for how long?” he said. I asked him how they are going to deal with the lack of funds in the meantime and he replied that he and his colleagues are trying to find ways which are not exactly official at the risk of having themselves held accountable by the home owners, the suppliers of food and other basic necessities and other employees of ESTIA.

Heath Cabot (2013:453), writes that the indeterminate effects of “aid encounters in the context of asylum procedures may give rise to a circumscribed agency” that attempts to overcome structural hindrances and institutional gaps. Is it through this agency, within the ‘capitalist cracks’, of people acting ‘in-and-against the system’ that arrival situations are being created, transformed and appropriated in Karditsa? How can/should beneficiaries position themselves in such a process? Which are the legal indeterminacies and how creative can moral praxis become?

Our fieldwork thus, revolves around the formal but mainly the informal infrastructures that are created through crossroads and despite off the structural hindrances of ESTIA.

Sources cited:

Cabot, H. 2013 “The social aesthetics of eligibility: NGO aid and indeterminacy in the Greek asylum process”. American Ethnologist 40(3): 452-466.

Holloway, J. 2010 Crack Capitalism. London: Pluto Press

Suggested reading:

Marry-Anne, Karlsen, M. Jacobsen Christine, and Khosravi Shahram. 2020. Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration: Taylor and Francis. With a chapter on Greece by Katerina Rozakou.

Share

Construction site for the maintenance of the walls and creation of green space, funding EU. Source: the authors.

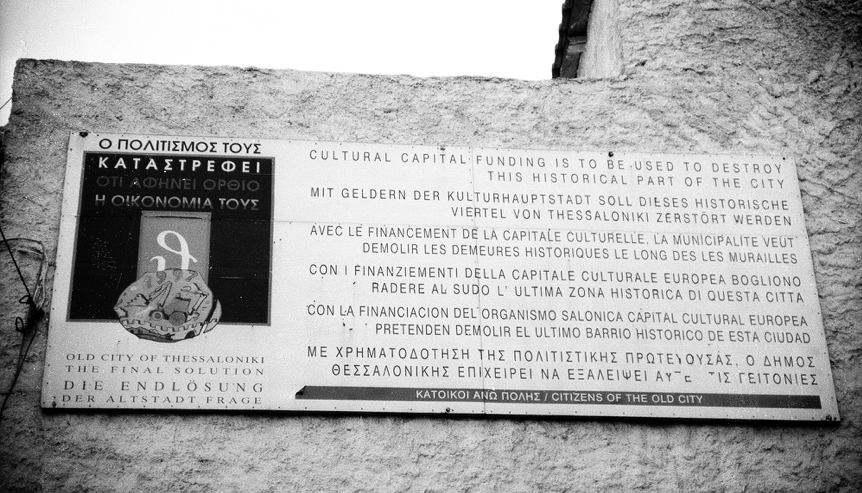

Label against the demolition of wall houses. Source: the authors (1999)

Graffiti in Ano Poli. Source: the author 2021

Wall houses in Ano Poli. Source: the authors.

by Charalampos Tsavdaroglou & by Zachos Valiantzas

October has just arrived and we have arranged a visit to a housing squat in Thessaloniki’s Ano Poli (upper town). A conversation with the dwellers of the squat will help us build trust and make contacts with more newcomers to the city. Our minds are filled with questions. Which are the material, social and political aspects of Arrival Infrastructures (A.I.)? What is the relationship between A.I., local and global history and the migrants’ everyday life? Our meeting is at 13:00 with a friend from Maghreb. We get in the car and park on Eptapyrgiou Street in a green space – under construction – next to the city walls.

These walls are the fortification which used to divide the palace area (Genti Koule) from the rest of the city. Almost 12 metres high now, the walls were initially built as a defensive infrastructure during the Roman and Byzantium era (4 th century) and various repairs and exapansions happened in the following years of the Ottoman Empire. The area around the walls was mainly inhabited by Muslim citizens until Thessaloniki city was occupied by the Greek army in 1912. After the Greek-Turkish war and more specifically as a result of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, 670,000 Greek citizens of Muslim religion moved from Greece to Turkey while 1,6 million Ottoman citizens of Christian religion moved from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace the other way around to Greece. About 200,000 Christians settled in Thessaloniki and several of them in the so-called ‘interchangeable buildings’, the residences built by Muslims who relocated to Turkey. Therefore, the area of Ano Poli was the place of arrival for the newcomers from Turkey, whose presence in turn attracted more refugees, relatives and friends of them, to settle or build makeshift accommodation – shacks – on the unstructured plots of the area around the walls.

One of the most distinctive characteristics of this new type of dwelling are the so-called “castroplikta” houses – wall houses, i.e small houses that are adjacent to or include parts of the Byzantine walls. However, only a small number of these “castroplikta” still stand today. In 1997, Thessaloniki was named the European Capital of Culture, which motivated a plan to demolish about 900 abandoned and inhabited wall houses in order to create a green zone 1 along the walls. The demolition program envisages the preservation of only 16 buildings, not as residential areas but as cultural and historical monuments of the refugees. We have witnessed local resistance to this demolition plan appearing in the public spaces of Ano Poli since our first visits in the fall of 1999. On one of our first visits to Ano Poli, this resistance took the form of a sign posted on a centrally located building next to the central Portara (a large door in the Byzantine walls) This sign used the same aesthetics, font and logo of the European Capital of Culture in order to attract the eyes of tourists. However, on second glance it turned the logo from a boat to a bulldozer and the message written in 6 languages stated “CULTURAL CAPITAL FUNDING IS TO BE USED TO DESTROY THIS HISTORICAL PART OF THE CITY”. Today, unfortunately, the sign is gone. While the demolition was considerably delayed, it eventually started to be implemented after 2010.

Having parked the car in this particular area of the demolished “castroplikta” houses, we head down to Osios David old church, where we arranged to meet our friend from Maghreb. During our way through the tiny cobblestone paths of Ano Poli, we see a slogan written on a wall: “immigrants welcome, tourists go home”. While we are looking at the slogan, some actual tourists pass by.

The slogan indicates the ongoing controversy over the right to Ano Poli. Similar slogans appear in the streets of the neighbourhood and call for an awareness about two interrelated issues: the increasing touristification and Airbnb-fication of the neighborhood on the one hand and the question of migrants’ and refugees’ housing on the other. There are dozens of similar slogans all over the neighborhood (in English and sometimes in Arabic) and, according to our discussion with local residents, the writers are often local residents – anarchists, leftists and migrants. Since 2016, after the closure of the Balkan Corridor, Ano Poli area has hosted several migrant newcomers, either as guests in solidarity residences, in apartments provided under UNHCR housing programs, or by occupying abandoned buildings such as the “castroplikta houses”. At the same time quite intense gentrification processes are taking place in the area. Searching the airdna database of Airbnb platform we found 1 about 250 available apartments and rooms in Ano Poli. Small hostels have also begun to appear.

1 According to our observations, in the area of Ano Poli there are several squats, housing projects and social centers. Our perception is that the slogans’ campaign (immigrants welcome/tourists go home) enriches and extends the discussion of similar campaigns across Europe beyond anti-airbnb sentiments and the touristification of cities or of specific neighborhoods. Indeed, the campaign in Ano Poli is not just a complaint against touristification but it proposes that the neighbourhood could be a welcoming place for – refugees and migrants – whose predecessors did built the area decades ago.

We meet our friend and he leads us to his housing squat. We realize that his house is one of the remaining “castroplikta” (wall houses) that is adjacent to the walls towards the side of Genti Koule.

There are two beds in the house and no electricity. Church candles are used for lighting, gas stoves for heating, and the interior is decorated with many teddy bears. Our friend welcomes us with a smile and a hug. We climb a makeshift staircase up to a small terrace where a sheet offers shading and a freshly-washed carpet has just been spread to dry. Our friend pours us vanilla-flavored tea with caramel and our conversation begins.

During our conversation we reflect upon the function of walls and how they typically signify a defence infrastructure in Europe, the US and other countries to prevent the entry of immigrants. We talk about fortress-Europe raising fences. Here, however, these old walls may allow us to think differently. Here, these walls reverse the above function and importance. Indeed, thinking with Stavros Stavrides’ ideas about common space as threshold space, these walls have become in some way threshold infrastructure: a shelter but also an entrance to the city for those who do not have papers.

As we continue our research in Ano Poli, together with residents, we will further explore this notion of threshold infrastructure and how it connects practices and narratives on urban commoning with the arrival infrastructures framework. 1 Airdna “tracks the performance data of 10M Airbnb & Vrbo vacation rentals. It offers short-term rental data analysis on Airbnb occupancy rates, pricing and investment research, and more” (airdna.co)

1 Airdna “tracks the performance data of 10M Airbnb & Vrbo vacation rentals. It offers short-term rental data analysis on Airbnb occupancy rates, pricing and investment research, and more” (airdna.co)

Share

THE UK’S PROPOSED MIGRATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PARTNERSHIP

Recently, the first steps were taken in implementing a bizarre new plan for processing arrivals across the English Channel. Announced on 14 April 2022, the ‘Migration and Economic Development Partnership’ (MEDP) was described by the Conservative government as an ‘innovative’ approach likely to become a ‘new international standard’ in dealing with asylum. The UNHCR, in contrast, has called it an ‘egregious breach of international law and refugee law and human rights law.’ It involves distinguishing between asylum claims on the basis of the claimant’s mode of arrival, and excluding from the asylum process anyone arriving outside ‘safe and legal routes.’

Since the ‘safe and legal routes’ currently in existence relate only to resettlement of refugees already living in safe third countries, their families, and various discretionary visa schemes (Home Office, 3 December 2021), the announcement expressed an intention to severely erode or eliminate the system of in-country asylum claims. From detail that has since emerged, in-country claimants will henceforth be affected by their connection to or stay in a third safe country, and considered for removal to that country or alternatively to Rwanda, a ‘safe third country’ with which the UK has signed an agreement. The most obvious targets of this new approach are arrivals across the English Channel, whose departures from the French coast give them an inevitable ‘connection’ to a third safe country.

On the day of the surreal announcement, Prime Minister Boris Johnson gave a speech at Lydd Airport, an air base to Her Majesty’s Coastguard located along the Kent coast in South East England. In it, he made a case for the MEDP policy, and the controversial Nationality and Borders Bill which underpins it (which passed into law two weeks later, on 28 April 2022). His rhetoric reminded me of Achille Mbembe’s observation that the ‘security state thrives on a state of insecurity, which it participates in fomenting and to which it claims to be the solution (Mbembe, Necropolitics, p.54). In this reflection from ReROOT’s UK field site, I share some thoughts on how the discursive choices in this speech conjured a state of insecurity, justifying and giving a ‘common-sense’ quality to the government’s decision to treat arrivals across the channel, and men in particular, as disposable and less deserving of rights.

Conjuring threats to life, law and governance

Boris Johnson’s speech at Lydd – which serves as an airbase for Her Majesty’s Coastguard – focused on ‘action to tackle illegal migration’ (Johnson, 14/04/2022). Johnson linked this action to the efforts of the Nationality and Borders Bill, for the first time, to “distinguish between people coming here legally and illegally” and to make that distinction material to claims and status.

What is clear from Johnson’s speech is how the invention of this distinction between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ arrival, allows the majority of asylum seekers to be named as ‘illegal immigrants’. Once this is accomplished, their arrival can be considered a crime and a threat to law and order, which the state can then claim to solve using the instruments of national security rather than of hospitality and humanitarianism.

The speech demonstrates the power of this legal/illegal distinction to mark as criminal the everyday and internationally recognised act of arriving in a territory with the intention to claim asylum. It speaks of in-country asylum claims as ‘a parallel illegal system’, of people arriving on boats or trucks as entering or arriving ‘illegally’, as having chosen ‘illegal options’ which constitute ‘abuse of our legal system.’ This despite the 1951 Refugee Convention stating that Contracting States ‘shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who… enter or are present in their territory without authorization, provided they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.’

Apart from 13 references to illegality, the speech emphasises the association of irregular migration with other criminal themes, such as ‘people smugglers’ (mentioned 8 times), ‘gangs’ (mentioned 7 times) and ‘abuse of the vulnerable’. The speech emphasises the ’vile‘, ‘appalling’, ‘ruthless’ and ‘brutal’ nature of these activities. It uses hyperbole to equate them with a ‘sweeping tide’ that might bring the ‘80 million displaced people in the world’ to the UK’s doorstep, expecting ‘the British taxpayer to write a blank cheque to cover the costs.’ The substantial costs of housing asylum seekers (£5million a day) are also cited, implying irregular asylum seekers are responsible for this financial burden, while contributing issues in housing and immigration policy and practice are overlooked.

Finally, the speech utilises multiple references to death and suffering: ‘desperate and innocent people… taken to their deaths in unseaworthy boats’, ‘drowning in unseaworthy boats’, ‘losing their lives at sea’, ‘suffocating in refrigerated lorries’, in such a way as to justify the Government’s approach, present it as ethically necessary and argue for it to be implemented with speed and urgency: it is imperative, it seems, to ‘stop these boats now, not lose thousands more lives.’

In this way, in-country asylum claims are presented as virtually inseparable from crime, deviance and death, leading to the extraordinary revelation that the Government’s solution to ‘taking back control of illegal immigration’ is ‘a long-term plan for asylum.’

Defining a New Trope for Disposable Life?

Having described the ‘innocent people’ who are ‘taken to their deaths in unseaworthy boats,’ it is a major leap to explain how these supposedly ‘innocent’ people become criminals undeserving of the chance to make an asylum claim if they are fortunate enough to reach British shores. It is as if they can only maintain their innocence if they die; if they live, they become lawbreakers abusing the UK’s asylum system, who (to prevent the deaths of other innocents) must be disposed of through deportation or removal to a third safe country.

To prevent the whole edifice of this ‘innovative’ new system from collapsing on this point, a new type of disposable human is produced. It is ‘men under 40’ that the Prime Minister’s speech appears to construct as the scapegoat for all the ills of uncontrolled immigration. In a dubiously evidenced statement, the Prime Minister claimed at Lydd that ‘around seven out of ten of those arriving in small boats last year were men under 40, paying people smugglers to queue jump and taking up our capacity to help genuine women and child refugees.’

This sweeping statement appears as a rhetorical device intended to draw a distinction between illegitimate, ‘queue-jumping’ male asylum seekers, and ‘genuine’ women and children claimants. As there are no publicly available statistics on asylum seekers’ method of entry, the veracity of this statement is difficult to judge in terms of the sex and age distribution of arrivals by boat, let alone the percentage of such arrivals that are ‘genuine’.

The statements immediately following this one go on to paint male claimants under 40 as illegitimate beneficiaries of the UK asylum system. Johnson asserts that they ‘should’ have claimed asylum in other countries and that their failure to do so is the cause of ‘rank unfairness’ in the asylum system. Coming from the Prime Minister, the claim that legitimate asylum seekers must be ‘DIRECTLY fleeing imminent peril’ statement sounds authoritative, but it contradicts legal precedent (see judgement of Lord Simon Brown in Adimi or for more on legal duties of non-penalisation, see this blog by Costello and McDonnell, 2021).

While ‘men under 40’ are only singled out once in the speech, it appears that here for the first time they are being produced as a distinct, unwanted and illegitimate group. Having defined ‘men under 40’ as those who ‘jump the queue’ and are not ‘genuine refugees’, the Prime Minister goes on to state that under the Government’s plans, ‘those who try to jump the queue, or abuse our system, will find no automatic path to settlement in our country, but rather be swiftly and humanely removed to a safe third country or their country of origin.’ And indeed, from news reports emerging with detail of the MEDP from anonymous official sources, the public has also heard that the plan would involve a pilot which would remove ‘single men’ to Rwanda and make them ineligible for refugee status in the UK (Lee & Faulker, BBC News, 18/04/2022), drawing critical commentary even from former Prime Minister and one-time Home Secretary Theresa May. In this combination of discursive and policy choices, it appears it is single men who come to occupy the position of ‘those who abuse our system.’

Having been produced as a disposable and undeserving category, is it really possible that single men arriving by irregular routes are to become the object of experimentation by policymakers, treated as a lower form of life that can be relegated to a place outside the terms of both domestic and international law? Certainly, theorists have argued that acts of exceptionalism are the very origin of sovereignty. In that sense, perhaps this is not so surprising. And the Nationality and Borders Bill has been controversial exactly for its intention to create a two-tier system that treats some asylum seekers as less equal than others (see blog by David Cantor, Eric Fripp, Hugo Storey and Mark Symes, and the Law Society’s submission to the UN’s universal periodic review of the UK). But even so, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.’ It does not allow men, single or otherwise, to be denied rights given to others. The UK’s Equality Act makes it unlawful to discriminate ‘against any person’ on the basis of their sex or marital status. To treat ‘single male’ asylum seekers differently from others would be to perform two prohibited acts at the same time.

When challenged about the criteria for removal in the weeks since the announcement, the Home Secretary refused to share specifics, arguing that to do so would provide ‘loopholes’ for smugglers to exploit. The recently published Equality Impact Assessment similarly avoids divulging specific criteria, insisting that decisions will be made on a case-by-case basis. Without transparency, there is little reassurance that in reality this policy will treat asylum seekers equally, particularly given the bias against men under 40 expressed in the Prime Minister’s Lydd speech.

The Home Office has since notified the first group of migrants of the intention to remove them to Rwanda under the MEDP. While the Government has claimed that this will save lives and reduce ‘human misery,’ over 160 organisations signed a letter calling it ‘shamefully cruel’ and likely to cause ‘immense suffering.’ Mbembe’s words are apt again in closing:

What, then, is this “borderization,” if not the process by which world powers permanently transform certain spaces into impassable places for certain classes of populations? What is it about, if not the conscious multiplication of spaces of loss and mourning, where the lives of a multitude of people judged to be undesirable come to be shattered? (Mbembe, ibid, p.97)

Share

Discussing future fieldwork in the Paou monastery. On Wednesday evening, technology was finally ‘under control’ and Marhabo, seated amidst an online and on-site audience could discuss her fieldwork in Istanbul in a relaxed hybrid setting

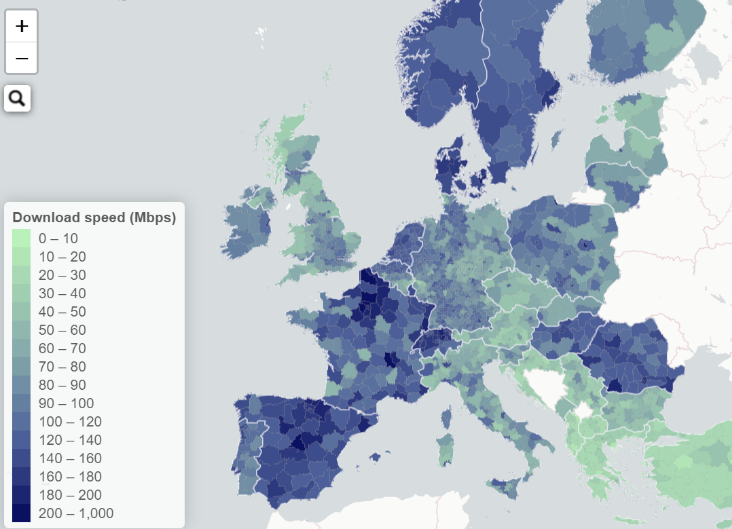

Unequal internet bandwidth in Europe. At the Paou monastery in Greece, average bandwidth was 14Mbps (down) and 1,3 Mbps (upload), which is not far from the regional average: in the village of Argalasti (where Paou is located), the bandwidth is on average 17,8mbps (down) and 2,2 Mbps (up) (Internet Speed in Europe (europeandatajournalism.eu))

Always use a headset to call in. Headsets filter out background noise and room echo.

Always carry a USB-stick to connect the material stored on the proverbial Fujitsu.

by Bruno Meeus

A few years ago, it was a quite revolutionary thing to ask the organisers of an academic meeting if you could give your presentation from a distance because of – for example – ecological, family or budgetary reasons. And it was even more difficult to ask a question or to expect to be really included in the discussion from a distance. The threshold to opt for an online rather than an on-site intervention now seems to have lowered because of Covid-19. Unfortunately, we are not there yet. For a fetishism is currently beginning to develop with far too much focus on razor-sharp images, high Wi-Fi speeds, dynamic cameras and what have you. A fetishism that leads to regular responses similar to: ‘no, a hybrid meeting is not possible’ and the piling up of ICT expenditures: ‘video conferencing cameras’ start at 1,000 euros, for the set-up of special hybrid conference rooms you do not get by on 5,000 to 10,000 euros. In what follows, I will first point out four important consequences of the exaggerated focus on ‘heavy equipment’ and then offer 10 tips for working with cheap and light equipment, as part of the general argument: ‘a hybrid meeting is always possible’. The tips are based on the experience of organising the first hybrid H2020 ReROOT meeting that took place between 11 and 18 September 2021 from the monastery of Paou in Greece. It is good to know that the technical preparations for this meeting had already been underway for a few weeks in order to avoid my own so-called technostress during the meeting, a form of stress I had been suffering from a lot during the past lockdown periods!

Why to avoid investing in expensive equipment

Images displace sound

The most logical effect of image fetishism: we forget the enormous importance of sound! There are now endless streamings, digital and hybrid meetings where the image is of high quality – where considerable investments have been made in the cameras – but where the central speaker is too far from the microphone, where someone’s laptop generates a continuous whistling sound throughout the meeting, where screaming feedback loops make you fear for permanent hearing damage, where the line of the microphone in the room is not linked to the softphone (Zoom, Teams, etc.) so that only the room can hear the speaker, etc. Of course there is the fact that you can quickly check whether you are ‘in the picture’, but that it is a lot harder to know whether something ‘sounds good’. Nevertheless, small adjustments – as I will indicate below – can make a world of difference. In Paou, where the image regularly slowed down or faded out, and where presentations kept ‘hanging’, it soon became clear that the meeting stood or fell with the quality of the sound.

Heavy equipment creates exclusions

Heavy equipment requires heavy equipment. Expensive cameras are useless in cases of lower Wi-Fi flows. It creates an unequal geography of well-connected places on the one hand, with all the necessary equipment in place for a ‘professional’ meeting and poorly-connected ‘amateuristic’ or ‘underdeveloped’ places where ‘a hybrid meeting is not possible’. This focus on images, on high flows, on well-equipped ICT rooms, means that a lot of participatory fieldwork in randomly Wi-Fi-ed meeting places seems impossible from the start. It reminds a bit of the image of the ‘business consultancy city’ Ash Amin is talking about in Telescopic Urbanism and the Poor: a networked but inward-looking exclusive urban world, the access to which is extended to ‘well-Wi-Fied’ homes, conference rooms, planes, fast trains etc.. On top of that there is the enormous amount of energy this heavy ICT-equipment requires.

Heavy equipment backgrounds maintenance work

Expensive and complicated technology means that, as a researcher, you soon think that the management of such a miracle belongs to the world of specialised logistic support, think: the technician in a dustcoat. That is a pity at a time when the divisive gendering, classing and racialisation of ‘thinking labour’ and ‘manual labour’ are increasingly under pressure. The work of the technician is unnoticed, unimportant, almost inexistent, when the meeting is going well1. The (job of the) technician only comes into the picture when something doesn’t work, or even worse, the technostress is then unloaded on the technician. The technician is then blamed for the failure of the meeting (instead of blaming the exaggerated expectations with regard to Wi-Fi and stability!)

Heavy equipment does not do your work

Expensive technology does not prevent voices from outside the room from being less ‘powerful’ in the conversation. An inclusive dialogue is not achieved by technology alone, but through the active shaping of equal speech positions using the technology at hand. Creating such an inclusive online/on-site platform for a conversation can only happen by actively monitoring whether all ‘stakeholders’ in the meeting are ‘on board’, both inside and outside the room, whether everyone can make themselves understood without being threatened and whether everyone can be heard. This requires a great deal of collective work that technology will not do for you – but which it can help you to do if you can manipulate it yourself.

10 tips based on the experiences in Paou

Tip 1: Use a headset to call in

Always speak through a headset (which can be simple earphones) when you are participating on-line in a hybrid meeting. A headset filters out a lot of background noise to begin with. Indeed, also in Paou, the sound of digital construction workers drilling through a wall somewhere else in Europe entertained the meeting for a while. And there is another advantage. Headsets cancel what is sometimes called ‘room’: the echo of your voice in the room where you are sitting. Even in a quiet room, speak into a headset rather than against the microphone of your laptop to project your voice more precise and direct. And that is important for the speakerphone we used in Paou (more about that in a moment). The speakerphone cancels echo, but does this best when the voice is well defined (and when you do not have an echo or ‘room’ of the room at home).

Tip 2: Use a speakerphone in the room and turn off all other sound!

The speakerphone is the miracle to bring every hybrid meeting to a good end very easily. In Paou, we used the cheapest speakerphone from Jabra which we connected to Teams via a laptop. All sending and receiving of images was organized via other laptops or phones. In such a setup we could ensure that there was at least a stable sound source during times when connectivity would fall under 1 Mbps. Talk to your ICT department and get yourself a cheap but decent speakerphone that you can plug into your laptop. With it, you can turn any meeting into a hybrid meeting where up to 25 people in the room – that was the situation in Paou – can participate. It is crucial that everyone else in the room who is logged into your Teams, Zoom or Skype meeting is fully muted. The best way is to mute via the hardware of the laptop: find the buttons on the keyboard to mute your speaker and microphone.

Tip 3: Chair with control over sound

Combine the role of chair with sound control, you can respond much faster to problems this way. Or divide the tasks in such a way that the chair and the person in control of the sound have constant visual contact in the room. When it is clear to everyone that you are in control of sound, you can immediately ask someone to speak louder or softer or to use a headset but also temper someone continuously dominating the discussion. In Paou, participants started coaching each other after a while. As chair in control of sound, you can open the microphone of someone who has been waiting a long time with a raised ‘old hand’ from a distance while listening to people convivially conversing in the room.

Tip 4: Designate avatars and always activate the chat

People from outside the room can designate someone in the room as an ‘avatar’, but you can also search for avatars yourself and attribute them in the room. In Paou, a number of people in the room got into the habit of keeping an eye on the ‘hands’ of the digital participants and signaling when someone from the digitals wanted to intervene. Of course, you can also encourage the people in the room to make parallel contact with those outside the room via Whatsapp or Signal or similar. The softphone’s chat function is essential for communicating with people outside the room: they can use it to launch their question, and as a chair you can give them guidelines without disrupting the discussion in the room. Moreover, the chat is the last resort if the sound fails. So make sure that the chat is always activated and in some way visible.

Tip 5: Avoid polycentric discussions at all times

It is almost inevitable that polycentric discussions will arise in larger groups. But avoid these conversations taking over, as this is completely unbearable for people outside the room, and certainly avoid these conversations being held next to or above the speakerphone. Again, messaging via Whatsapp and Signal are an elegant way of organising polycentric discussion in the room without disturbing the sound. Moderating is therefore very often pointing out to people that they are making it impossible for others to understand the conversation, and occasionally encouraging people to speak a little louder. Related to this: stimulate the people with the loudest voices to move a little further away from the speakerphone. This also applies to metaphorically loud (or dominant) voices.

Tip 6: Find a workhorse for streaming images

Although the start of my argument might suggest otherwise, I would like to emphasise that images are of course important. Capturing, sending and projecting images does, however, require a stable computer, especially when you are concatenating sessions of 2.5 hours in a row, as in Paou, where continuous streaming was organized between 9:00AM and 6:30PM. It quickly became clear that an everyday laptop could not handle that. Fortunately, there is always a geek around with a Mac and/or other robust computer and when you point out the exceptional ‘workhorse’ capacities of this computer to the owner, then it should not be a problem to let the images run through that computer. In Paou, that meant that a relatively old Macbook provided continuous projection from Wednesday onwards and the built-in laptop camera captured the audience. If you want more diverse viewpoints on the room, an external webcam – or a linked smartphone via the app EpocCam, for example – instantly expands the possibilities for visualising the room (but take 8 and 9 into account).

Tip 7: Make sure you have connectors for HDMI and VGA

Imagine a situation where people want to show a presentation from their own laptop. In Paou, we had two options, each time starting from the situation that you’re presenting with a shared screen in Teams (or Zoom or whatever). Either you present from Teams and someone else in the room projects your shared screen on the wall through Teams. In Paou, this option regularly failed so that nobody – neither the people in the room, nor the people at a distance – could see the presentation. What did work: connecting your own laptop through the projector in the room, logging into Teams, and giving the presentation for the room – directly to the projector in the room – and for the people at a distance with your screen shared in Teams. However, this also regularly ran into problems. Many laptops only have a port for HDMI or one for VGA or none at all. It is worth the effort to bring a few intermediate connectors to an event like this. But there is another solution.

Tip 8: USB connects the proverbial Fujitsu

While there is always someone with a Mac, there is also always someone with the proverbial Fujitsu, in this particular case a Fujitsu with a worn-out keyboard and taped CD-ROM port. In such a case of man-machine entwinement, a golden rule applies: USB is the master connector. Don’t try Wetransfer, Bluetooth or Airdrop or logging into Teams, but go straight for the USB stick.

Tip 9: Use cables when possible

You can connect the speakerphone to your phone or laptop with Bluetooth. This can be useful when, for example, you are filming with your smartphone and connecting to Teams, allowing you to capture the sound 6 metres away without having to worry about cables. In Paou, this turned out to be an excellent solution for streaming a workshop that took place around a long row of tables. But in most cases, it pays to be simple: with a minimal investment in an active USB cable, you can connect your devices 10 metres further without having to worry about the battery of your phone or speakerphone, or about disturbance of the Bluetooth connection as a result of interference of nearby refrigerators, microwaves, Wi-Fi routers and others.

Tip 10: Broadcast the presentation where the connection is most stable

And to end nicely on 10 tips: we discovered a final trick on day 5. When the Wi-Fi connection in the room is not that stable, ask someone else at a distance, with a stable Wi-Fi connection, to load the PowerPoint into Teams and present from there. It turned out to be piece of cake for the Dortmund team to give a duo presentation with someone on-site in Paou and someone on-line in Dortmund.

Extra: some statistics

At the Paou monastery, average bandwidth was 14mbps (down) and 1,3 mbps (upload), which is not far from the regional average: in the village of Argalasti (where Paou is located), the bandwidth is on average 17,8mbps (down) and 2,2 Mbps (up) (Internet Speed in Europe (europeandatajournalism.eu))

Here is a handy overview of bandwidth requirements for different forms of hybrid meetings (from sound to razor sharp images)

Microsoft Teams bandwidth requirements and other FAQs (2021) (checkmybroadbandspeed.online)

Share

Flyer installation Zaandam – photo made by author

Broeders verheft u ter vrijheid – foto van website Dries Verhoeven, copyright Willem Popelier

THE FUTURE OF HUMAN LABOUR

The old ammunition factory on the Hemburgterrein in Zaandam forms the perfect theater for the mysterious and dystopian art installation by Dries Verhoeven. From 1896 until 2003 people produced weapons, artillery and munition for the Dutch army. With this history still in the atmosphere, the sound of an old ceremonious song, coming from the speaker of a white van, leads you to the entrance of the former factory. Walking through a cheerless and dark hallway, we find a glass room in which labourers sing Brothers, exalt thee to freedom! on loop. Behind the glass room, blinking robot arms move pallets, work that used to be done manually. After thirty minutes the alarm goes, the singers get 5 minutes to stretch their legs. Then it starts all over. Hours on end.

Dries Verhoeven wants the visitors to think about the purpose of working bodies in the contemporary world. Farmers replace Dutch workers with labourers from Central and Eastern Europe. At the same time, companies use algorithms, robots and other AI to get the largest profit margin. After all, computers work even harder than labour migrants.

Agriculture is also one of those sectors where machines take over parts of manual labour and people have to do the thankless tasks that cannot (yet) be done by robots. What does this mean for the thousands of seasonal labourers that come each year to work in the greenhouses of the Netherlands, or in the orchards in Belgium? Do their labour circumstances change? And how do labour migrants themselves feel about this? Do seasonal labourers change their plans for the future and start looking for other places or sectors to work and make three times the amount money they can make in their home country? This year I will try to answer these questions (and many more) by doing research in the Westland area (NL) and the Haspengouw region (BE). Dries Verhoeven and the eight Bulgarian performers who sang this labour anthem for hours and days on end without understanding the lyrics, give some preliminary food for thought.

De oude kogelfabriek op het Hemburgterrein in Zaandam vormt het perfecte theater voor de mysterieuze en dystopische installatie van Dries Verhoeven. Van 1895 tot 2003 werkten mensen hier aan de productie van vuurwapens, artillerie en munitie voor het Nederlandse leger. Met deze geschiedenis nog steeds voelbaar en zichtbaar op het terrein, leidt het geluid van plechtig gezang, afkomstig uit de luidspreker van een wit busje, je naar de ingang van de voormalige fabriek. Na een kale, donkere gang treffen we een glazen kamer waar werknemers achtereenvolgens Broeders, verheft u ter vrijheid! zingen. Op de achtergrond verplaatsen piepende robotarmen pallets, werk dat vroeger met de hand werd gedaan. Na dertig minuten gaat de zoemer af, krijgen de zangers 5 minuten pauze. Daarna begint het weer opnieuw. Uren achter elkaar.

Dries Verhoeven laat de bezoekers hiermee nadenken welk nut onze werkende lichamen tegenwoordig hebben. Tuinders vervangen Nederlandse werknemers met arbeiders uit Centraal– en Oost– Europa. Tegelijkertijd zoeken bedrijven met algoritmes, robots en andere AI die 24/7 werken naar de grootst mogelijke winstmarges. Computers werken immers nog harder dan arbeidsmigranten.

Ook in de landbouw nemen machines delen van het handwerk over en mensen hebben de ondankbare taak om klusjes over te nemen die (nog) niet door apparaten kunnen worden uitgevoerd. Wat betekent dat voor de duizenden seizoensarbeiders die ieder jaar naar de kassen in Nederland komen, en de fruitboomgaarden in België? Veranderen hun werkomstandigheden? En wat vinden arbeidsmigranten daar eigenlijk zelf van? Veranderen seizoensarbeiders hun toekomstplannen en zoeken zij andere plekken of sectoren om hard te werken en drie keer zoveel geld te verdienen als in hun herkomstland? Aankomend jaar probeer ik die (en nog veel meer) vragen te beantwoorden door onderzoek te doen in het Nederlandse Westland en het Belgische Haspengouw. Dries Verhoeven en de acht Bulgaarse performers die dit arbeidslied urenlang zongen zonder de tekst te begrijpen bieden alvast stof tot nadenken.

Wanneer het geluid van de bewegende machines niet de oorverdovende overhand heeft, komt het meerstemmige socialistische strijdlied als een geluidsmuur op je af. Kijkend in de ogen, ietwat ongemakkelijk, van een van de ‘arbeiders’ in de ogen, hoor je dat het inderdaad een meerstemmig lied is. Het verhaal van seizoensarbeid is alleen te begrijpen door te luisteren naar individuele stemmen en de verhalen die zij vertellen.

De ‘levende’ voorstellingen zijn helaas al voorbij, maar de ‘making of’ tentoonstelling is nog tot 15 augustus te bezoeken in West Den Haag.

Share